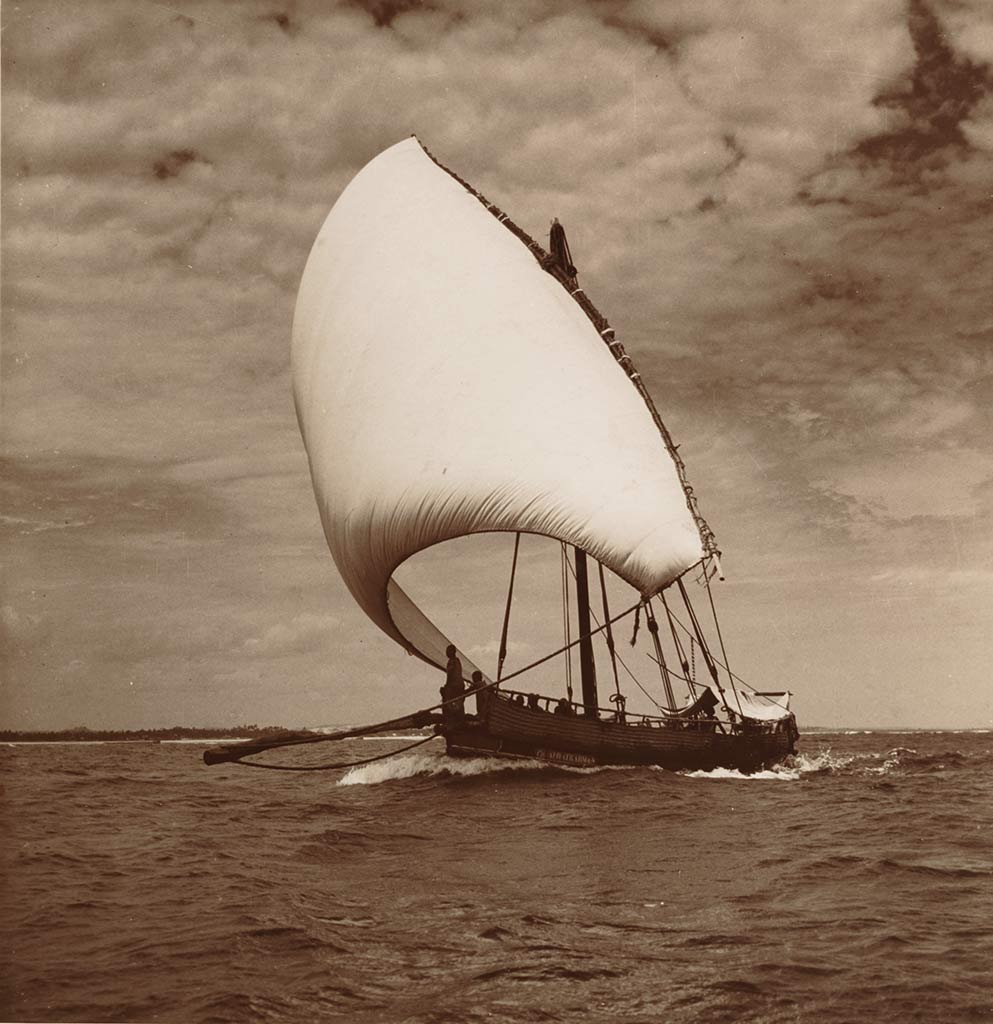

Monsoon Dhows

Sailors have harnessed the Indian Ocean’s monsoon winds for at least two millennia. The Swahili term “dhow” encompasses a diversity of sailing ships, from coastal fishing boats to ocean-going vessels. Dhows drew the cosmopolitan urban communities of Indian Ocean world together. The seasonal patterns of monsoons meant that sailors would stay in distant ports for months at a time. They took sojourns in the cities of east Africa and the Horn, the Arabian Peninsula, Persia, India, and beyond to China, Sumatra and Java. Dhow routes created intricate loops of cultural exchange – gold and cotton, migrants and merchants, and marriages that tied together people from distant lands. Indian Ocean cities and their citizens continue to reflect the long duration of this cultural dynamism.

[ read more ]